The CIO & AFL Battle to Represent 25,000 Workers at South Portland Shipyard

PHOTO: Women shipyard workers during WWII, Portland, ME

Welder Arthur Lebel of Richmond was just 28 when he was hired by the militant Industrial Union of Marine Shipbuilding Workers (IUMSWA), CIO to organize 25,000 workers in the South Portland shipyards at the height of World War II. He observed how brutal and unjust factory work could be before they became unionized. Back then, it was a time when “union” was a dirty word and the boss was “king.”

“You may come to work on a morning and find that your job was gone because the foreman sold it to someone else,” Lebel recalled several years later. "Or if you didn't buy a cheap watch off'n the foreman, you'd be fired.”

Lebel recalled how bosses sought to exert complete control over workers, even in their personal lives. While he was growing up, his father Pete Lebel worked at the Hyde-Windlass company in Bath producing deck machinery for ships. One day, the foreman fired his father because he refused to hand President Herbert Hoover's picture up in the window of his home. When the superintendent heard about it, he made sure his father was kept on the job, but other workers weren’t so fortunate when it came to domineering supervisors.

Workplace safety was also abysmal before workers had a collective voice on the job. When his father worked as a buffer at Hyde-Windlass, there was nothing on the machine to protect him and all of the bronze dust blew right in his face. His lungs eventually broke down due to all the bronze dust he inhaled into his lungs and he died young as a result.

By the time Pete’s son Arthur began working at BIW, welder were working in tanks welding galvanized iron that would give off a thick smoke that carried zinc oxide and other toxic fumes. Before there was even an official union at the yard, union activists successfully pressured management to install a $50,000 ventilating system to suck out the fumes and force in fresh air. After the workers formed their union, they fought for other protections in the shipyard while national unions successfully lobbied for better workplace laws in Washington.

“Companies are the same now as they always were, they're in business for a profit, and they wasn't so anxious about the safety conditions of their employees,” Lebel told the interviewer in 1972. “Workers had to want these things and they had to fight for them.”

Lebel and his welding brothers were unsuccessful in winning the election for the CIO at BIW in 1941 as the more conservative workers decided to go with a more company friendly independent union. After getting a leave of absence from the yard later that year, he helped workers at the Todd-Bath shipyard in South Portland win their union election the following year. However, the achievement was tempered when the AFL’s Metal Trades defeated the CIO a few months later in the South Portland Shipbuilding Corporation’s (SPSC) West Yard.

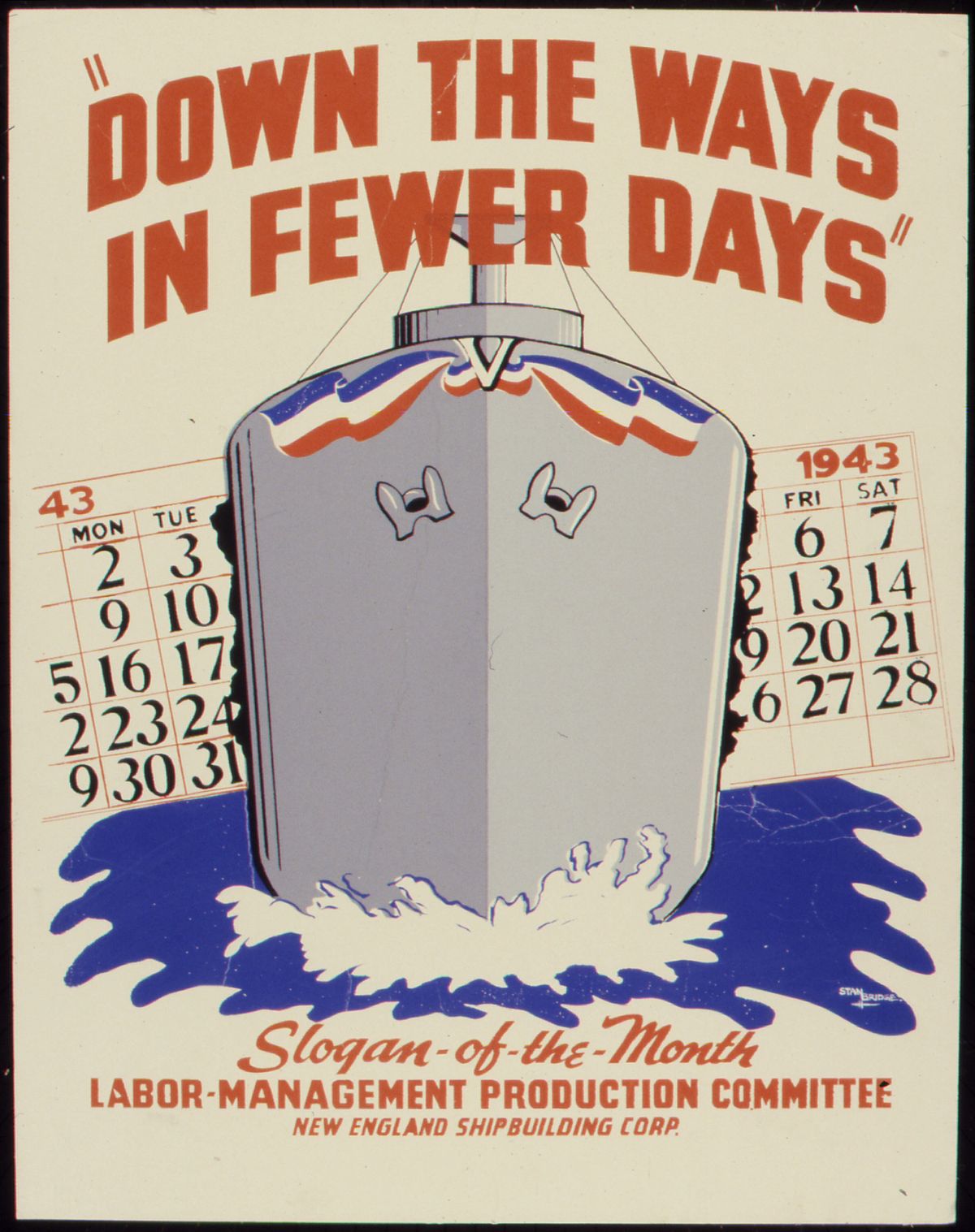

The same month the Metal Trades ratified their first contract, Todd-Bath’s East Yard and the West Yard merged to form the New England Shipbuilding Corp. (NESC) — the fifth largest emergency shipyard in the nation with 25,000 workers. Naturally, this posed all kinds of problems for the workers as both unions claimed to represent the same workers and that their contracts were still valid.

As soon as rumors began spreading about a potential merger, the IUMSWA, CIO began enthusiastically gathering thousands of signed union cards at the West Yard and petitioned for a new NLRB election for the whole yard in October, 1942. The AFL was alarmed because they knew their election victory was helped by the fact that the yard hadn’t been running at full capacity and conservative craft construction workers outnumbered CIO supporters on voting day. By the time the SPSC contract was ratified in July, 1942, the SPCC workforce had grown to 9,000 workers and was expected to reach 12,000 by the end of the year. The AFL also knew that the CIO had a strong shop floor organizing strategy.

"It is next to impossible for us to continue to reach the unorganized through our present system, bearing in mind that the CIO has permanent organizers at work here, and we are getting ours done on a voluntary basis,” one AFL official complained.

The AFL appealed to the NLRB to stop the election, but were denied because the workers were all now on the same payroll. The NLRB ruled that the AFL needed to prove it truly represented the workers since a comparatively small number of workers were employed at SPSC when the earlier election was held. The board also wanted to resolve highly publicized delays in production caused by jurisdictional fights between the two unions over whose work was whose.

Admiral Emory Scott Land, Chairman of the U.S. Maritime Commission, which oversaw contracts for ships at the yard, was widely quoted in the press as stating that the SPSC’s West Yard had the lowest production rate of any shipyard in the nation with wages lower than Todd-Bath’s East Yard. However, at the end of the war, Land sent telegram calling Bath Iron Works President Pete Newell, who also headed up the South Portland Shipbuilding Corporation, a “top-flight shipbuilder, an A-1 industrial leader, and a loyal friend."

As Maine labor historian Charlie Scontras noted in his book Labor in Maine: Building the Arsenal of Democracy and Resisting Reaction at Home, 1939-1952, the CIO boasted that its contract in the East Yard was “a model for shipyards everywhere." It claimed that the AFL had copied it, but was unable to enforce it. As a result, CIO noted that IUMSWA Local 50 workers at Todd-Bath were better paid and its stewards had a far stronger say in workers classifications than in the AFL’s Metal Trades.

In addition, Local 50 had won back pay for workers and eliminated a staggered shift. It also argued that workers preferred its emphasis on rank and file democracy and contrasted it to the AFL’s more top-down bureaucratic structure. Unlike in the AFL craft unions, which appointed officials, CIO workers democratically elected their stewards and other union officials.

The CIO blasted the AFL’s craft system as “DIVIDE AND RUIN” because it divided workers into as many as twenty different crafts. The AFL constantly red baited the CIO, but the CIO dished anti-patriotic accusations right back.

"Since we are all American . . . why does the AFL DISCRIMINATE against RACE, CREED, and COLOR!! (To us it STINKS like a bit of HITLER'S DICTATORSHIP!),” read one incendiary column in the Yard Bird, Local 50's newspaper.

Local 50 also had to combat misinformation from AFL supporters who claimed if the CIO won representation for the whole merged yard, it would fine former AFL members. Other false rumors spread that workers would have to continue to work under the AFL contract if the CIO won. The CIO countered that once the AFL’s high initiation fees and “racketeering” practices used to collect them were driven out, its contract would also be null and void. The CIO also accused AFL officials of helping to get pro-CIO workers fired.

Some workers expressed support for the CIO because it had a lower initiation fee and fixed dues than the AFL unions. Local 50 claimed that a CIO membership book could transfer to all other shipyards without payment or additional fee. The AFL membership book, on the other hand, was only good at the South Portland shipyard and they would have to pay another initiation fee if they switched jobs.

The AFL, which first organized in Maine in the 1890s, emphasized its “local” roots in its slogans like "Vote for Maine—Vote A.F.L.” By characterizing CIO organizers as “outside agitators” and "cutthroats who invaded Maine from New York and New Jersey,” it tried to whip up xenophobic sentiment about the progressive union and capitalize on a traditional suspicion of outsiders among many Mainers. The AFL further accused management of supporting the CIO by placing IUMSWA organizers on its payroll, which made it possible for it to gain access to the names and addresses of all workers for campaign purposes.

"We all know, of course, that the CIO Shop Stewards are getting paid not only by the union but by the company, because it is common knowledge that a CIO Shop Steward gets the top pay in all departments,” the AFL’s Shipyard News claimed.

The AFL also blasted the wage and classification system that IUMSWA negotiated that allowed the company to save “millions of dollars.” The AFL proposed what it called the “Progressive Plan” in which workers would receive automatic raises as opposed to the management’s favored classification system. As Scontras explained, under the AFL’s plan, if a worker started out at a certain base pay per hour, after so much time the worker would automatically receive a new classification at the next highest scale and the process was repeated. The Progressive Plan, the AFL argued. would eliminate all "viciousness and politics” from the worker classification process as workers would not be subject to the whims of a a shop steward or company supervisor.

Then in the fall and winter of 1942, two unauthorized strikes over a new pay schedule deal between the Metal Trades and the company. The company forwarded the pay schedule to the War Labor Board, but several months later the new wage rates still hadn’t come and workers were getting impatient. More than a thousand craft union workers took part in the wild cat strikes, which rocked SPSC’s West Yard and dealt a massive blow to the AFL’s hopes of keeping its 9,000 members together.

Read the first eight installments of our series covering the Origin Shipbuilders’ Unions in Maine:

- Part 1: 90 Years Later: Local S6 & the Spirit of the CIO Part 1

- Part 2: The First Union Formed at Bath Iron Works

- Part 3: Maine Workers & the March to World War II

- Part 4: Maine Workers Mobilize for Wartime Production in WWII

- Part 5: When "The Hicks Beat the City Slickers” in the BIW Union Election of 1941

- Part 6: When BIW Welders Launched a Wildcat Strike

- Part 7: Welders Continue to Wage Wartime Wild Cat Strikes

- Part 8: Organizing the South Portland Shipyards